Mushroom Benefits and Biology

Mushroom Benefits and Biology

So you’re thinking that mushrooms might be a great addition to your food plan, and possibly even your medical supplies. Good for you! Mushrooms are a wonderful way to add a layer to both. While not the easiest organism to grow, mushroom cultivation has its rewards. The challenge for one thing; if you can grow these you can grow just about anything! Additionally, they’re actually pretty low maintenance once established. No watering or weeding is required!

Home Cultivation Has Many Benefits Over Foraging

- more predictable harvests

- the mushrooms you want to have, as opposed to taking what Nature gives

- year-around availability

- weather dependency: too much fluctuation can mean no harvest at all

- critters: they love the mushrooms too and Nature is first come, first served

- toxicity: unless you’re really good at identification, it can be easy to consume the wrong shroom, with deadly effects

The Health Benefits of Mushrooms are Many!

Culinary mushrooms are great sources of protein, fiber, antioxidants, B vitamins, copper, potassium, and many other micronutrients. They’re also very low in calories, saturated fats, and sodium. Research is ongoing with respect to some mushrooms’ ability to fight cancer and inflammation, and modulate the immune system. Mushrooms can act as a potent probiotic, stimulating gut health, in addition to neuroprotective effects. Other medicinal uses include as antibacterial agent and cholesterol lowering. Reishi mushrooms are held as especially good medicine, helping with all of the above along with liver/kidney disease, respiratory disease, viral infections including HIV/AIDS, fatigue, and pain associated with shingles outbreaks. Some are also useful in a process called bioremediation, cleaning up polluted sites by internalizing the pollutants within their own bodies. It should be noted that mushrooms used in this way shouldn’t be eaten, however.

Culinary mushrooms are great sources of protein, fiber, antioxidants, B vitamins, copper, potassium, and many other micronutrients. They’re also very low in calories, saturated fats, and sodium. Research is ongoing with respect to some mushrooms’ ability to fight cancer and inflammation, and modulate the immune system. Mushrooms can act as a potent probiotic, stimulating gut health, in addition to neuroprotective effects. Other medicinal uses include as antibacterial agent and cholesterol lowering. Reishi mushrooms are held as especially good medicine, helping with all of the above along with liver/kidney disease, respiratory disease, viral infections including HIV/AIDS, fatigue, and pain associated with shingles outbreaks. Some are also useful in a process called bioremediation, cleaning up polluted sites by internalizing the pollutants within their own bodies. It should be noted that mushrooms used in this way shouldn’t be eaten, however.

So, What About the Biology?

While this may be considered boring technical scientist stuff, it’s my opinion that the more you know, the better you grow. This applies to both vegetables and mushrooms. So read on!

While this may be considered boring technical scientist stuff, it’s my opinion that the more you know, the better you grow. This applies to both vegetables and mushrooms. So read on!

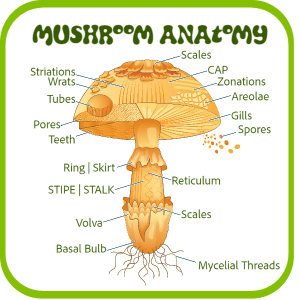

The mushroom that we eat is actually a sexual reproductive structure. The organisms producing them are fungi (sing. fungus) and their big thing in life is to reproduce. Most mushrooms are taxonomically Basidiomycetes, a fungus whose spores develop in a structure called a basidia. These structures are located inside of the gills, usually on the underside of the mushroom but not always. When the mushroom matures, the cap opens up and drops all of those spores in order to propagate the species. Those spores, once inoculated into a suitable medium, grow into a structure called a hypha (pl. hyphae). This system of hyphae are collectively called mycelia (sing. mycelium). They merge sexually and form a primordia (sing. primordium), which is also called a pin. The process of the pin growing into the fruiting body we’re looking for is called pinning. That pin will develop into the fruiting body, aka mushroom, and be harvested.

Fungi can be saprotrophic, mycorrhizal, or parasitic. Parasitic fungi grow within a host, often killing it in the process. Mycorrhizae form a symbiotic relationship with plants, improving nutrient uptake in the process. Saprotrophs consume organic decaying matter, such as trees. Mushrooms that grow on decaying trees fit this category, such as shiitake. A great many species of interest grow in this way. Fungi, with some exception, don’t possess chlorophyll so they don’t photosynthesize. They have to absorb nutrients in other ways. The mycelia function in this way much as plant roots function.

Common Names of Fleshy Macrofungus Groups

Mushrooms: Fleshy, fragile, with gills, stipe present or absent

Boletes: Fleshy, fragile, tubes instead of gills, tubes separable from caps

Polypores: Dry, tough, woody, rarely fleshy, tubes that are not separable from cap, often lacking a stem

Tooth fungi: Fleshy or woody, spines or teeth on underside of cap or hanging from a branches system and lacking a cap

Chanterelles: Fleshy, fragile, with long decurrent gill-like folds, wrinkles, or ridges, or smooth on underside of often vase-shaped cap

Coral fungi: Fleshy, fragile, single or multiple erect branches

Stereoid fungi: Mostly tough, leathery, some fragile, stem with fan-shaped cap, underside of cap smooth, bumpy, irregularly poroid, folded

Jelly fungi: Moist, gelatinous, variable shapes from globular to coral to toothed

Crust fungi: Thin, soft, or tough, flat against the substrate which is usually logs, spore-producing surface smooth, bumpy, poroid, or wrinkle-folded

Puffballs: Fleshy at first, dry and papery when mature, white fleshy inside becoming olive-brown dry and powdery. Spores ejected through central pore in the sac when the sac is disturbed

Earthstars: Fleshy at first, dry and papery or woody with age, in essence a puffball attached in the middle of a thick-fleshed covering that opens and spreads out in a starlike pattern

Earthballs: Fleshy at first, then dry and thick-skinned, opening irregularly but not by a discreet central pore, developing black greasy spores that become powdery with age.

Bird’s nest fungi: Felty, woody, or leathery cups filled with lentil-shaped “eggs” on dead wood/wood chips

Stinkhorns: Fleshy, fragile, phallic-shaped stalks with slimy, smelly coating over the tip, or cage-like, claw-like, or flower-like with smelly slime coating on the inner parts, often on woody substrates

Cup fungi (discomycetes): Fleshy, large or small, cuplike fruit bodies or fruit bodies finger-like, saddle-shaped, brain-like, sponge-like, and all on a stalk, plate, saucer-shaped, or rabbit ear-shaped.

Stromatic fungi (pyrenomycetes): Fruit body very small, requiring hand lens to properly visualize, globular or flask-shaped, with minute pores (perithecium); fruit bodies clustered on and mostly in a fleshy or dry charcoal-like stroma; stroma is variously colored white, pink, red, green, grown, or black, and variously shaped as erect finger-like structures, cusions, balls, or crusts covering and parasitizing other fungi, like mushrooms, boletes, or polypores, or on dead woody plant materials.

Preferred Habitat

Ah, now we’re getting somewhere! As living organisms, the fungi that produce mushroom have needs, both in terms of nutrients and habitat. That’s what we’re providing when we cultivate them: a nice place to live and yummy things to eat, and in return they fruit for us, at least in theory. So where do they like to live and what do they eat?

Ah, now we’re getting somewhere! As living organisms, the fungi that produce mushroom have needs, both in terms of nutrients and habitat. That’s what we’re providing when we cultivate them: a nice place to live and yummy things to eat, and in return they fruit for us, at least in theory. So where do they like to live and what do they eat?

Light

Remember, fungi don’t photosynthesize. Therefore, they don’t need a lot of light in their environment. Since dark spaces have the added benefit of moisture retention, basements and other dark places can be ideal for growing. This will vary by species however: oysters, shiitake, enotaki, lion’s mane, and maitake all want some light during the fruiting stage so full dark isn’t the best choice for them. Buttons like cool, dark places while wine caps prefer partial shade.

Moisture | Humidity

These are not the same thing! Moisture is a measure of water in the liquid state while humidity is a measure of water in the vapor state. The substrate you select should hold a good amount of moisture without being dripping, soggy wet. If you squeeze some in your hands and get lots of water, your substrate is too wet. You don’t want it to dry out either! It’s worth noting that some mushrooms on logs will need to be soaked in drums of water during dry spells, to keep them from drying out.

Air retains humidity best when it’s warm, so having a warm space is best for fruiting. This is a necessary condition of fruiting in fact, so some will place their substrates under a humidity tent and spritz with a small water bottle several times per day. Humidity tents are as easy as a plastic bag over wooden BBQ skewers. A plastic spray bottle kept handy works wonders and is very cheap.

Temperature

The temperature mushrooms in general require vary from 10-25 Celsius/50-80 Fahrenheit, so basements in climates that go subzero may not be the best choice in winter. The colonization process is more forgiving than the fruiting stage, since growing requires far less energy than reproducing. Room temperature is usually good for colonization; the parameters needed for successful fruiting will depend upon the species and sometimes, by strain. Reference books are very helpful in this regard.

Nutrients

Mushrooms need specifically: proteins, fats, starch, nitrogen, and lignin. Lignin is a basic component of wood, which is why many mushrooms grow well on logs. Others prefer compost substrates, and a few will even grow on toilet paper rolls! Spawn is often made from a cereal grain such as rye berry, while sawdust blocks are fortified with wheat bran for the nitrogen. The exact combination and sources of these nutrients again, varies by species. Again, books are good.

These days I prefer physical books to the Internet. The reference list contains several wonderful choices but is by no means exhaustive.